Docker, Kubernetes, and Helm — Intuitively and Exhaustively Explained

An in-depth guide to the technologies powering modern application infrastructure

In this article, we’ll explore how sophisticated backend environments for complex applications can be efficiently managed and scaled using Docker, Kubernetes, and Helm.

From the highest level, Docker allows you to package your code into something called a “container”, a fully self-contained and portable unit of software that can be duplicated and run pretty much anywhere. Kubernetes allows you to manage how these containers are applied to resources at scale, coordinating them into complex, interrelated applications. Helm adds an additional layer of abstraction on top of Kubernetes by bundling these interconnected components into reusable, shareable packages called charts, making it far easier to develop and re-use complete systems.

When used together, these three technologies transform backend infrastructure into a modular system of building blocks that you can mix, match, scale, and rearrange with remarkable flexibility. This power of abstraction is why virtually every major organization uses the three technologies to manage their backend infrastructure.

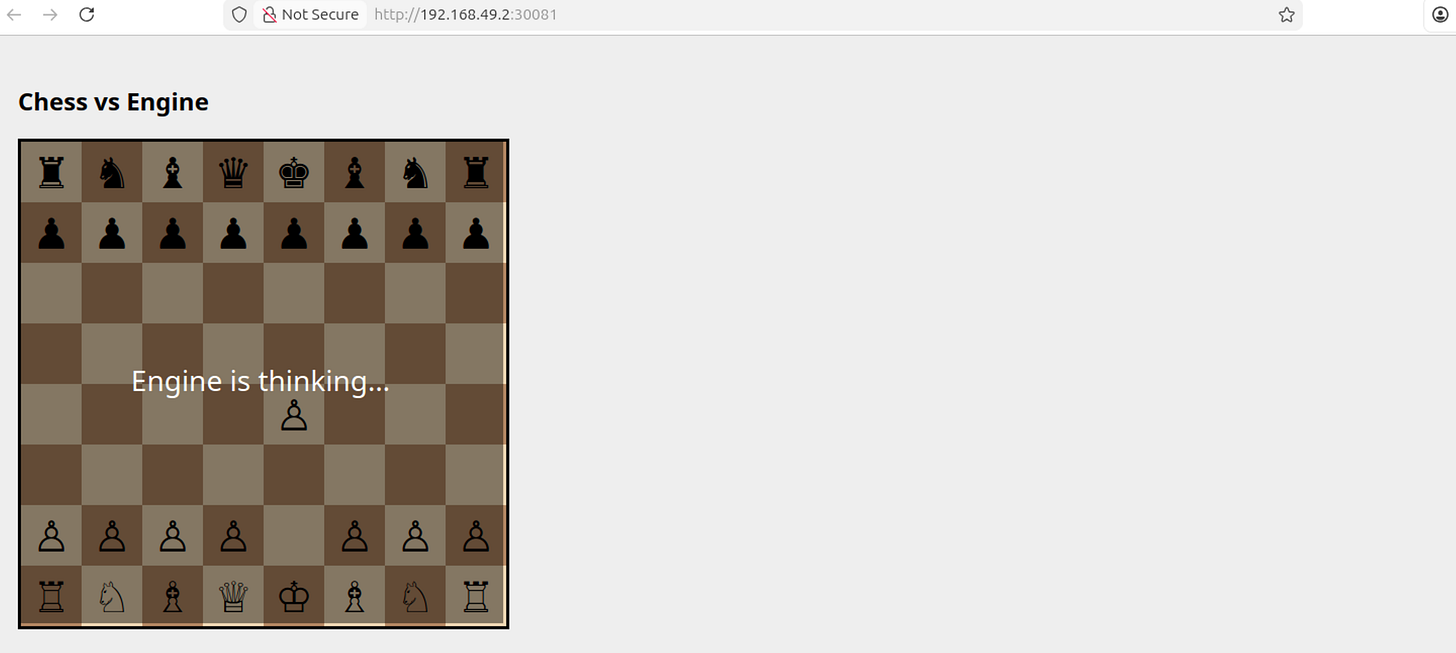

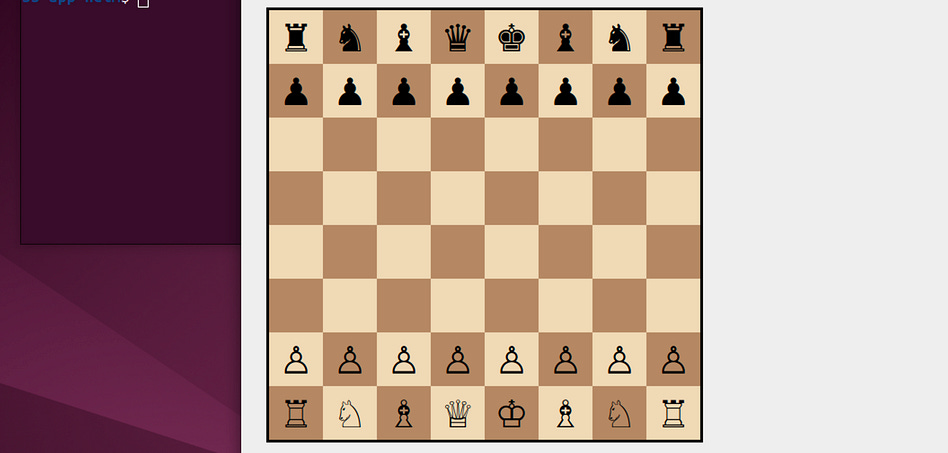

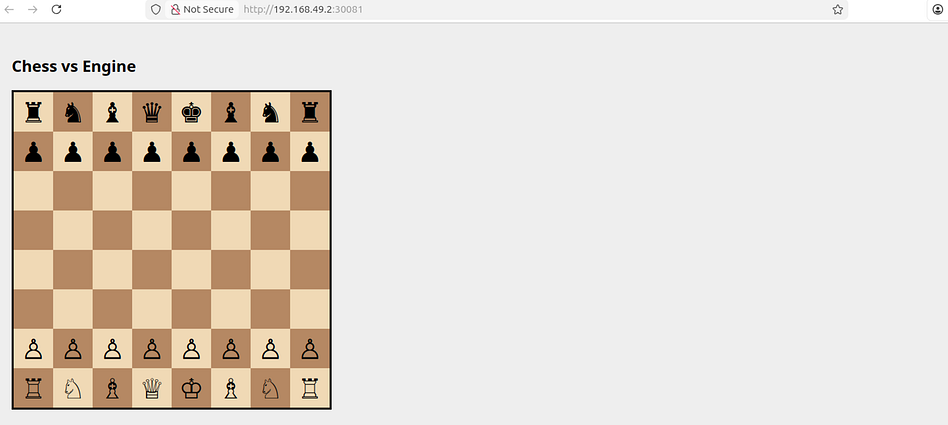

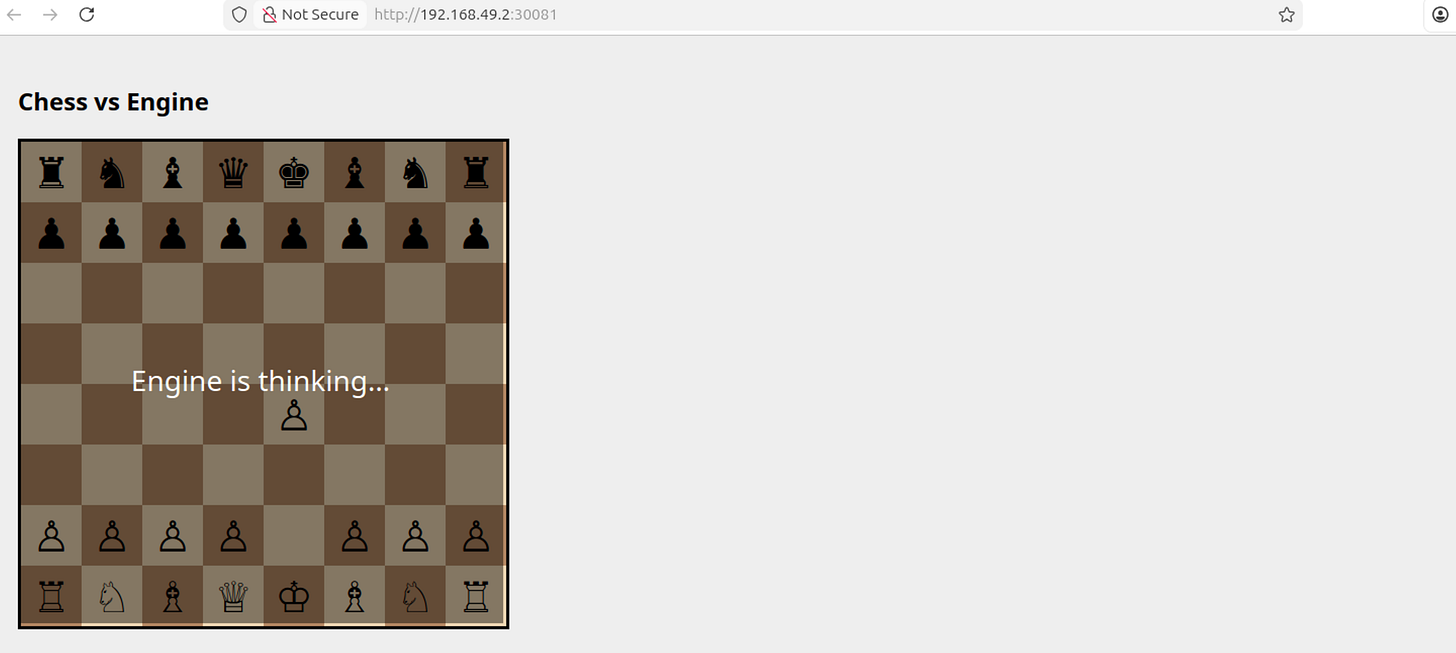

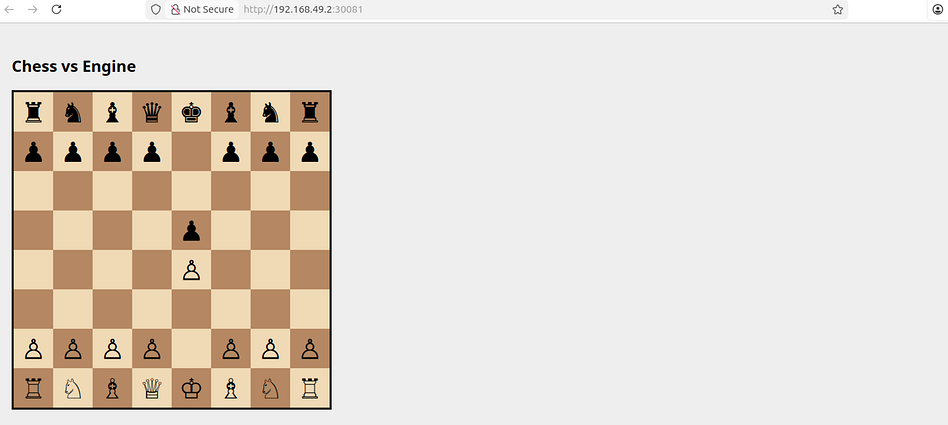

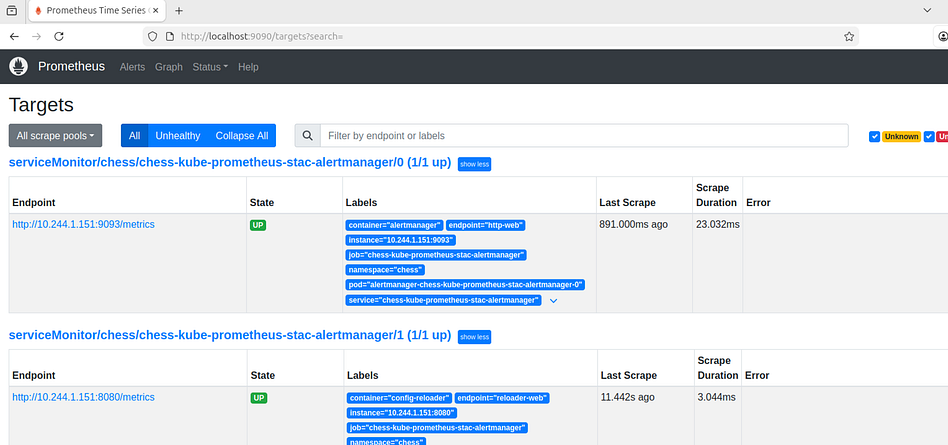

There’s a ton of depth to this topic, which isn’t realistic to explore “exhaustively” in a single tutorial. If you build an application with Kubernetes, you’re going to have to do some googling along the way. That said, we will form a solid conceptual understanding of the three technologies by building two demo applications: one that can estimate digits of pi at scale, leveraging numerous machines in a cluster to do it, and another that exposes a chess application with a simple database and workers which run a chess engine. Both of these are simplifications of very real-world use cases that large companies use Kubernetes for on a daily basis.

[init] Waiting for 10 worker pods to complete...

No resources found in default namespace.

[init] Workers finished: 0/10

No resources found in default namespace.

[init] Workers finished: 0/10

No resources found in default namespace.

[init] Workers finished: 0/10

[init] Workers finished: 2/10

[init] Workers finished: 10/10

[init] All workers completed, starting reducer.

[reducer] Collecting results from: /results

[reducer] inside_total = 863939569

[reducer] points_total = 1100000000

Distributed π estimate: 3.141598432727273

Who is this useful for? Anyone interested in building an application that serves large numbers of users, or processing large amounts of data, with multiple computers working together in a robust and scalable manner.

How advanced is this post? This is designed to be a first exposure to containerization with Docker, orchestration with Kubernetes, and deployment with Helm. That said, the technology is complex, and I’m skipping through a lot of the application logic and focusing on the orchestration and deployment side. Thus, this article may feel a bit abstract for more junior developers.

Prerequisites: Anyone can read this article and get a general understanding of the topic. Realistically, though, you should probably be somewhat comfortable with building at least simple full-stack applications to get the most out of it.

The Case For Learning on a Virtual Machine

While the power of these technologies exists on the cloud, I want to avoid setting up a cloud account and racking up a thousand-dollar AWS bill because we accidentally overallocated resources. We’ll be experimenting with the technology locally so we can get comfortable. As a result, following along with this tutorial might require a bit of configuration.

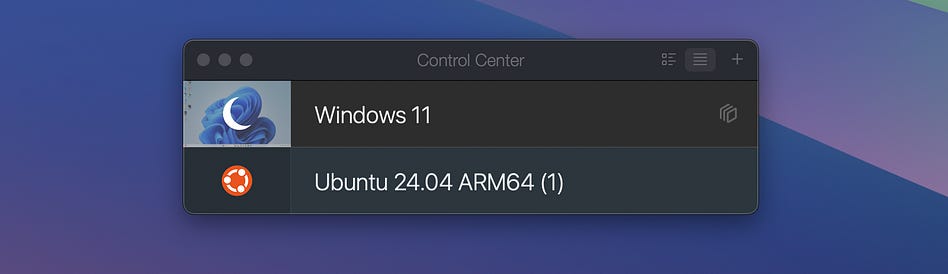

A big reason I avoid local configuration in tutorials is because of discrepancies about how your computer is set up, vs how my computer is set up. To help mitigate those issues, I tend to use an emulator that I can use to spool up new operating systems, then tear them down again, making it very easy to start from scratch. This isn’t sponsored, but I use Parallels Desktop on Mac to do this type of stuff. When I open Parallels Desktop, I can create or access various virtual computers within my computer.

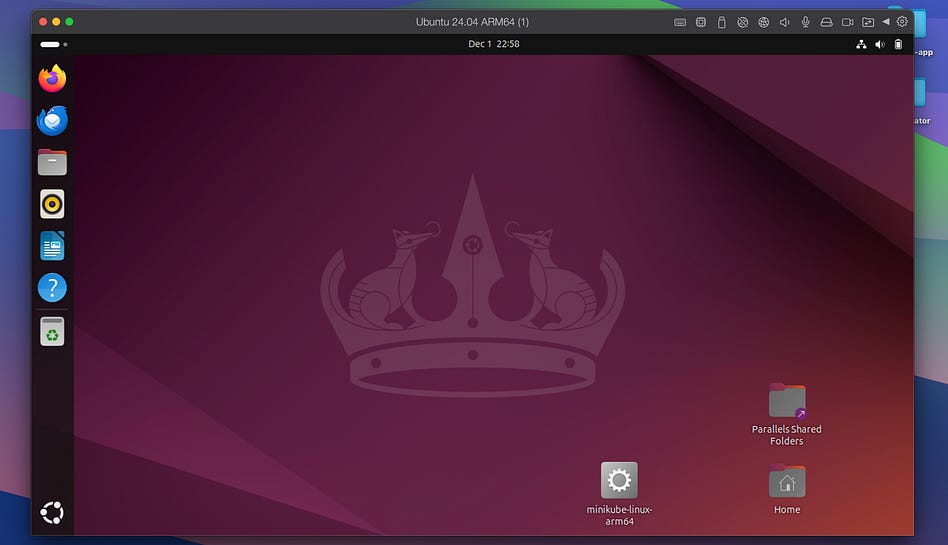

I can open up Ubuntu, for instance, and I have a little Ubuntu Linux machine on my computer.

If I make some changes to this computer, for instance by installing packages, and I want to try again from scratch, I don’t have to do anything complicated. I can simply go back into Parallels and create a new Ubuntu system from scratch.

This is really powerful for me as a writer, because it helps me make sure I’m not forgetting to mention some setup process because I already did it on my computer a few months ago. It can be powerful for you, as a learner, because it minimizes the likelihood of something going wrong because you didn’t realize you made a change to your computer a few months ago.

There are numerous emulators available on most major operating systems. Some of them are free, and some of them are paid. Whether you use an emulator or not, you should be able to follow along, though the steps to install might differ slightly based on your operating system.

Setup

To get started, we’re going to need to install a few things. I’ll be assuming you’re in a Linux environment like Ubuntu. If not, you might need to do some googling to find the equivalent approach for you.

Setup 1) Installing Docker Engine

On Mac and Windows, it’s common to install Docker Desktop, but on linux it’s a bit quirky, and it’s more common to install the Docker engine directly via the command line.

Open up a terminal. First, it’s recommended to run this:

sudo apt update

sudo apt install ca-certificates curl gnupgThis updates the list of packages your Linux machine can install, and installs a few packages that Linux will use to securely install Docker.

Then run this:

sudo install -m 0755 -d /etc/apt/keyrings

curl -fsSL https://download.docker.com/linux/ubuntu/gpg | sudo gpg --dearmor -o /etc/apt/keyrings/docker.gpg

sudo chmod a+r /etc/apt/keyrings/docker.gpgIn essence, this downloads a trusted key from Docker, which can be used to secure Docker installation on your machine. This isn’t that important for us right now, but Docker being secure is very important for the big business that use it regularly, thus there’s a significant layer of protection even within docker installation.

Now run this:

echo \

“deb [arch=$(dpkg --print-architecture) signed-by=/etc/apt/keyrings/docker.gpg] https://download.docker.com/linux/ubuntu \

$(. /etc/os-release && echo “$VERSION_CODENAME”) stable” | \

sudo tee /etc/apt/sources.list.d/docker.list > /dev/nullThis adds Docker’s official software repository to the package manager on your Linux computer. Once you do that, you can run this:

sudo apt update

sudo apt install docker-ce docker-ce-cli containerd.io docker-buildx-plugin docker-compose-pluginwhich actually installs Docker. You can now verify that Docker is installed successfully by running

sudo docker run hello-worldWhich will return the following

Unable to find image ‘hello-world:latest’ locally

latest: Pulling from library/hello-world

198f93fd5094: Pull complete

Digest: sha256:f7931603f70e13dbd844253370742c4fc4202d290c80442b2e68706d8f33ce26

Status: Downloaded newer image for hello-world:latest

Hello from Docker!

This message shows that your installation appears to be working correctly.

To generate this message, Docker took the following steps:

1. The Docker client contacted the Docker daemon.

2. The Docker daemon pulled the “hello-world” image from the Docker Hub.

(arm64v8)

3. The Docker daemon created a new container from that image which runs the

executable that produces the output you are currently reading.

4. The Docker daemon streamed that output to the Docker client, which sent it

to your terminal.

To try something more ambitious, you can run an Ubuntu container with:

$ docker run -it ubuntu bash

Share images, automate workflows, and more with a free Docker ID:

https://hub.docker.com/

For more examples and ideas, visit:

https://docs.docker.com/get-started/We’ll dive further into Docker throughout this tutorial. If you want a sneak peek, you can get an idea of what’s going on by reading this output.

Setup 2) Installing Kubectl

Kubectl is a command-line tool for communicating with and managing “Kubernetes clusters”. We’ll explore what a “cluster” in Kubernetes is later. For now, it’s enough to know that Kubectl is necessary to do stuff with Kubernetes, so we need it on our computer.

This installs kubectl:

curl -LO “https://dl.k8s.io/release/$(curl -L -s https://dl.k8s.io/release/stable.txt)/bin/linux/amd64/kubectl”

chmod +x kubectl

sudo mv kubectl /usr/local/bin/And this verifies that it’s been installed:

kubectl version --clientYou should get something like this:

Client Version: v1.34.2

Kustomize Version: v5.7.1If you don’t, you might need to install for a different CPU architecture, for instance, by running this:

curl -LO “https://dl.k8s.io/release/$(curl -L -s https://dl.k8s.io/release/stable.txt)/bin/linux/amd64/kubectl”

chmod +x kubectl

sudo mv kubectl /usr/local/bin/You can find more instructions for installing kubectl here.

Setup 3) Installing MiniKube

MiniKube is designed to allow you to run Kubernetes on a single machine. The whole point of Kubernetes is to run an application that’s distributed across many computers working together, but local deployment is convenient for senior devs who want to test out changes they’ve made on their computer. It’s really useful to us because it means we can play around with Kubernetes without needing to set up any cloud subscriptions or buy a bunch of hardware.

Just like the last command, you might need a slightly different install based on the architecture of your CPU. For me (running on Apple silicon, which is ARM-based), this does the trick

sudo apt-get install -y conntrack

curl -LO https://storage.googleapis.com/minikube/releases/latest/minikube-linux-arm64

sudo install minikube-linux-arm64 /usr/local/bin/minikubeWe can make sure it’s set up by running

minikube start --driver=dockerWhich should get us an output that looks something like this, emojis and all.

😄 minikube v1.37.0 on Ubuntu 24.04 (arm64)

✨ Using the docker driver based on user configuration

💣 Exiting due to PROVIDER_DOCKER_NEWGRP: “docker version --format <no value>-<no value>:<no value>” exit status 1: permission denied while trying to connect to the docker API at unix:///var/run/docker.sock

💡 Suggestion: Add your user to the ‘docker’ group: ‘sudo usermod -aG docker $USER && newgrp docker’

📘 Documentation: https://docs.docker.com/engine/install/linux-postinstall/Setup 4) Installing Helm

It’s hard to appreciate why Helm is necessary, given the fact that we haven’t dived into any of the other technologies yet. Basically, it will make it easier for us to manage and reuse existing Kubernetes. Installation is super easy:

curl https://raw.githubusercontent.com/helm/helm/main/scripts/get-helm-3 | bashRunning this afterward

helm versionshould result in something like this

version.BuildInfo{Version:”v3.19.2”, GitCommit:”8766e718a0119851f10ddbe4577593a45fadf544”, GitTreeState:”clean”, GoVersion:”go1.24.9”}Now that we installed everything, it’s probably a good idea to get a sense of what it all does. We’ll start with Docker.

Why Containerization, and Containers vs Virtual Machines

Docker allows you to package your application, and everything it needs to run, into a portable and repeatable unit called a container. This general process is called “Containerization” and is important for building robust and scalable backend applications.

Imagine you wanted to build a web service that converts videos to gifs in Python. You might find some library called super_video_to_gif , install it on your computer, and then build a server around that library. Great. You make it into a little GitHub repo that has all your dependencies listed out in a requierments.txt file. All you need to run your application on a computer is to do something like the following:

git clone https://...myrepo

cd myrepo

pip install -r requierments.txt

python run main.pyYou hop onto AWS, run those commands, and oh no. Your pip install failed. Turns out the super_video_to_gif requires Python 3.10, and the AWS machines have Python 3.8 installed. So you change your install script to update Python. That works for a while until AWS updates some defaults on their computers, and it turns out they upgraded some package that super_video_to_gif relied on, and it isn’t compatible with the new version.

Etc.

Hopefully you get my point. Any time you make any change, you need to debug a bunch of incompatibilities. Even worse, if AWS updates something under your nose, you might find your application randomly stops working. This general fragility is what Docker chiefly attempts to avoid. By bundling everything together in a neat little package, it ensures that if a Docker container did run, it will run again, and will do so reliably across many machines. A big concept that empowers this is “base images”.

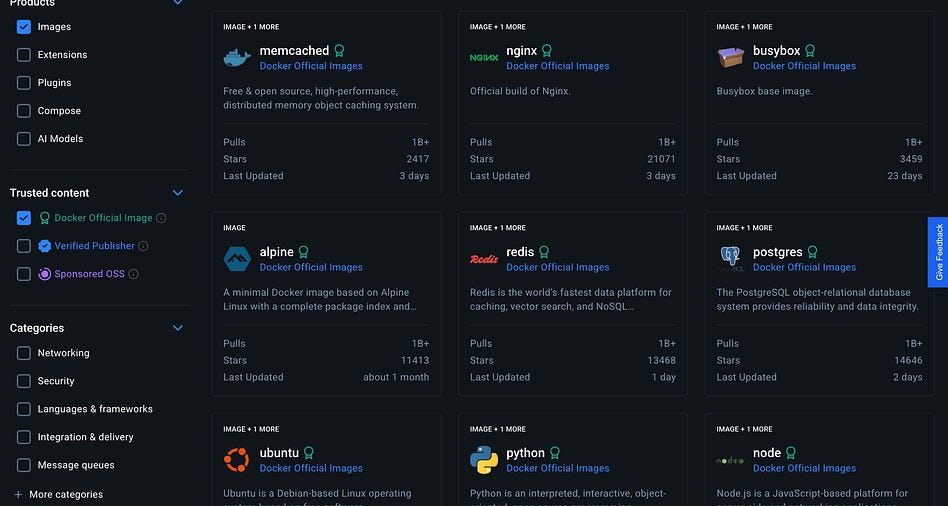

When you go to build a fancy Docker container, you do it by building on something that’s already predefined. Each of these base images has a file system with things like system libraries and runtimes already installed.

If we were developing our fancy video-to-GIF backend server, we might choose to use the official Python image, so that we know we’re always starting from the same place. Then, if we cloned our repo, installed our dependencies, and ran our application, we could do it with the confidence that we know exactly which version of Python we have, because it’s whatever Python version comes with the image.

You might be thinking this sounds like the virtual machine concept I introduced at the beginning of this article. Recall I’m spooling up virtual machines to help me explore this concept, and I can reproduce steps from scratch by installing a new virtual machine. Virtual machines and containerized images share a lot of conceptual ties, but they’re different in a few key ways that I’d like to briefly explore.

A Virtual Machine is very much like a virtual computer within your computer:

It has a kernel, which is the core of whatever operating system you’re using.

It has its own drivers, which can interact with the hardware on your computer: keyboard, mouse, speakers, screen, network adapters, etc.

It has all your files and installed applications.

It has its own virtualized representation of resources, like RAM, storage, and CPUs.

As a result, VMs are very, very isolated from one another. This is extremely useful if you want to run very different software stacks, experiment with risky tools, or keep workloads completely separated. But with this benefit, they come with two major drawbacks:

They’re heavy: You need to download an entire operating system image, which can be several gigabytes in size.

They’re slow: You need to boot and run that operating system inside your existing operating system, meaning you’re essentially doubling up on everything; two kernels, two sets of drivers, two full environments running simultaneously. Even with good virtualization support, this adds noticeable overhead.

Containers address these drawbacks by taking a different approach.

Instead of virtualizing an entire computer, containers reuse the host machine’s kernel. They only package the application and requirements needed to run the application; things like the runtime, libraries, configuration, and filesystem. This makes containers dramatically lighter and faster than VMs; they can start in milliseconds, take up a fraction of the space of a VM, and scale far more easily. Their environment is still isolated and reproducible, but not as completely independent as a full VM because they rely on the host’s kernel and drivers.

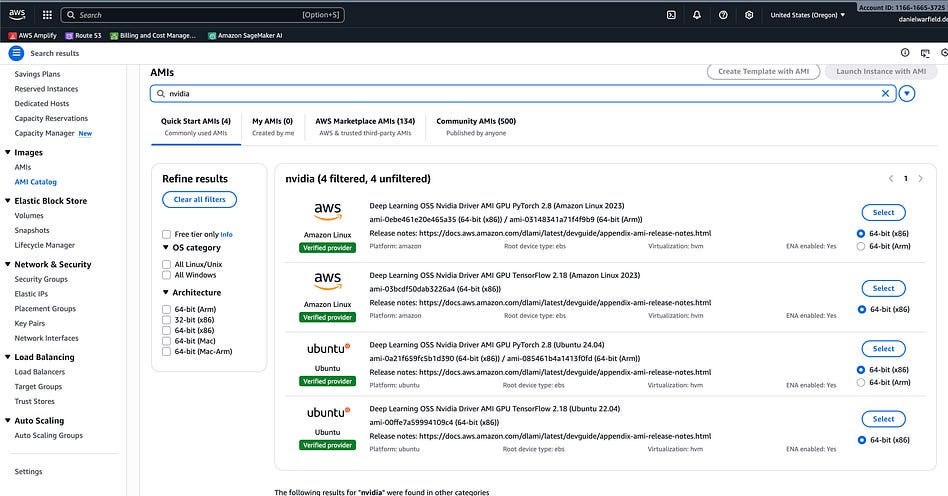

This does have the tradeoff that containers are not perfectly isolated from the host machine. Containers abstract a lot, but if you need a certain GPU driver to run your application, that won’t be helped by using a specific Docker image, because Docker images don’t handle GPU drivers.

Cloud providers make this problem easier by having standard definitions for hardware that you can build off of. Depending on your application, you may need to think outside of the container and consider the actual machine that is hosting your docker image.

This is pretty advanced, and out of scope of this article, but you could find yourself making these considerations if you were, for instance, deploying GPU accelerated AI workloads within your Docker container. For our purposes, Docker images can be thought of as consistent enough. In many applications, that is indeed the case.

What is a Docker Image, and How Do I Make One?

Great question. A Docker image is, essentially, a specific way to containerize an application. There are a few different approaches to containerization, but Docker is the most popular.

First, you develop your applications like you normally would. For instance, you can imagine a simple Python application called my-hello-app, which consists of a single Python script called hello.py within the src source code directory.

my-hello-app/

└─ src/

└─ hello.pyInstead of running hello.py based on whatever version of Python is on our machine, we can define something called a Dockerfile within our application. Typically, this is done outside the source code directory, because it works on the source code, and thus doesn’t belong in the source code.

my-hello-app/

├─ Dockerfile

└─ src/

└─ hello.pyThis Dockerfile will include instructions on how the docker image, which is wrapped around our application, should be built. Here’s an example of what our Dockerfile might look like:

FROM python:3.10-slim

# Set a working directory inside the container

WORKDIR /app

# Copy your entire src/ folder into the container

COPY src/ ./src/

# Run the main script

CMD [”python”, “src/hello.py”]Basically, what this Docker file says is that it will be based on the python:3.10-slim base image, A working directory within that image called /app will be created, and then the src/ directory of our application will be copied to the ./src/ directory of the image. We just created a working directory called /app, and . means the current working directory, so we’ll be copying our code into the /app/src/ directory within our image.

When we say CMD [“python”, “src/hello.py”], we’re specifying the default command that will execute when we actually run our Docker image, which is to run src/hello.py via python, assuming we’re within the /app current working directory. There are a few ways to define the default thing our container actually does when it gets started. This is one of the approaches.

Now that we have a Dockerfile defining how a Docker image ought to be built around our application, we can actually build the image by opening a terminal to our my-hello-app directory, and running.

sudo docker build -t hello-python .This means we’ll build a Docker image based on the Docker file in ., which is in my-hello-app. We’ll assign that image a tag, which is hello-python. You might notice that, after running, nothing gets created. That’s because, by default, images are stored across various folders in Docker’s managed file system. If you wanted to save it to a single file, you could do so by running

sudo docker imagesWhich will return something like this

IMAGE ID DISK USAGE CONTENT SIZE EXTRA

hello-python:latest 0e6f976ab46f 208MB 45.2MB These are all the Docker images that have been created. You might notice that hello-python is followed by :latest. This is a tag. We didn’t specify a tag, so Docker, by default, assigned a tag of latest to the build. You can assign other tags, for instance dev, qa , and prod to align docker containers with a CICD pipeline, but for now we’ll just keep things basic with the defaults.

If we want to actually run our built container, we can do so by running

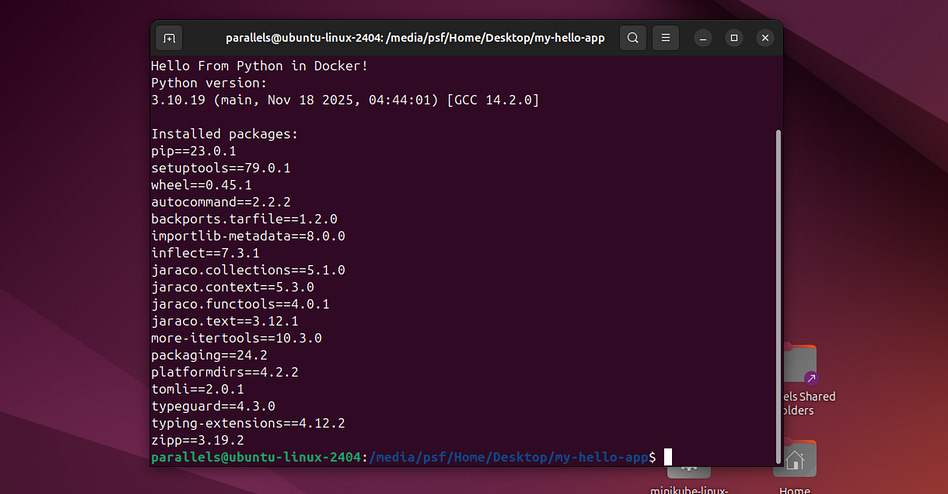

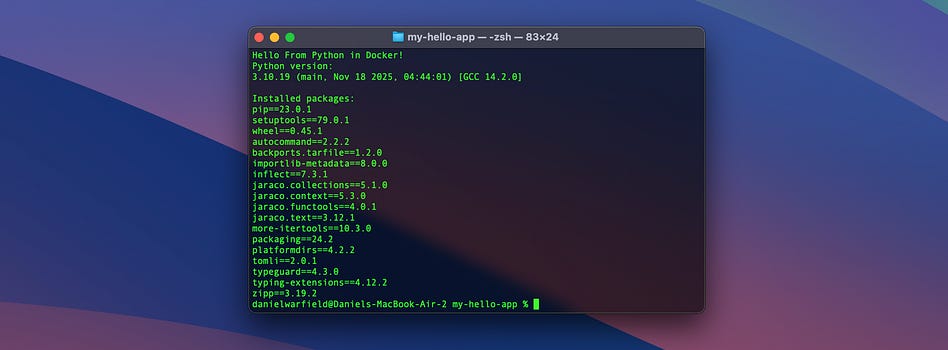

sudo docker run --rm hello-pythonThis runs our image (with the default tag, latest). Also, --rm automatically deletes the container after it stops running. The Python script in our Docker container simply prints out the current Python version and spits out all the dependencies. Running it results in:

Hello From Python in Docker!

Python version:

3.10.19 (main, Nov 18 2025, 04:44:01) [GCC 14.2.0]

Installed packages:

pip==23.0.1

setuptools==79.0.1

wheel==0.45.1

autocommand==2.2.2

backports.tarfile==1.2.0

importlib-metadata==8.0.0

inflect==7.3.1

jaraco.collections==5.1.0

jaraco.context==5.3.0

jaraco.functools==4.0.1

jaraco.text==3.12.1

more-itertools==10.3.0

packaging==24.2

platformdirs==4.2.2

tomli==2.0.1

typeguard==4.3.0

typing-extensions==4.12.2

zipp==3.19.2We just built and ran a docker container! That’s cool and all, but what’s really cool is that we can move this to a completely different operating system, and we’ll get the same result. I can export the Docker image into something called a tar file, via

sudo docker save -o hello-python.tar hello-pythonthis specifies the output file with -o , and saves our hello-python (default :latest) to that file. Now our directory contains the following

my-hello-app/

├─ hello-python.tar

├─ Dockerfile

└─ src/

└─ hello.pyI’ve been doing all this in my Linux VM.

But we can copy this hello-python.tar file onto a Mac, for instance, and load it by running

docker load -i hello-python.tarWhich will load the image onto docker on my mac. I can then run the Docker image on my mac with

docker run --rm hello-pythonAnd, lo and behold, I get the same exact output I got on my linux machine.

Which is pretty cool. No installation, no configuration, same exact output.

We’re just scratching the surface with Docker, but often the surface is all you need. It handles containerization, so you don’t have to. We’ll explore more sophisticated Docker tricks as necessary later in the article. For now, though, we can move on to exploring Kubernetes.

Jumping into Kubernetes (K8s)

First of all, Kubernetes is a long word, and is often abbreviated into “k8s”, because there are 8 words between the “K” and “s”. Is Kubernetes plural? Is it’s singular form “Kubernete”? Does it matter? I guess not. What matters is that Kubernetes is often abbreviated as either K8 or K8s. I have a tendency to flip-flop between the two.

Kubernetes (K8s) is a system for automating the deployment, scaling, and management of containerized applications. Basically, if you have a bunch of hardware, you can use K8s to manage which containers are running and how they work together, allowing you to build sophisticated applications that operate across multiple computers.

Instead of speaking theoretically, we’re going to jump right into an example application. We’ll describe a problem, build a containerized solution with Docker, and deploy it with k8s. Once we have some understanding of k8s, we’ll then explore Helm.

All code for all examples in this article can be found here

Sample Problem Definition, Calculating Digits of Pi.

My boy Archimedes just hit me up, apparently he got a slick new MacBook Air, and he wants to use it to help him calculate an approximation of pi. He’s not very tech savvy, and he asked for our help. We don’t need to use Kubernetes for this, but what the heck.

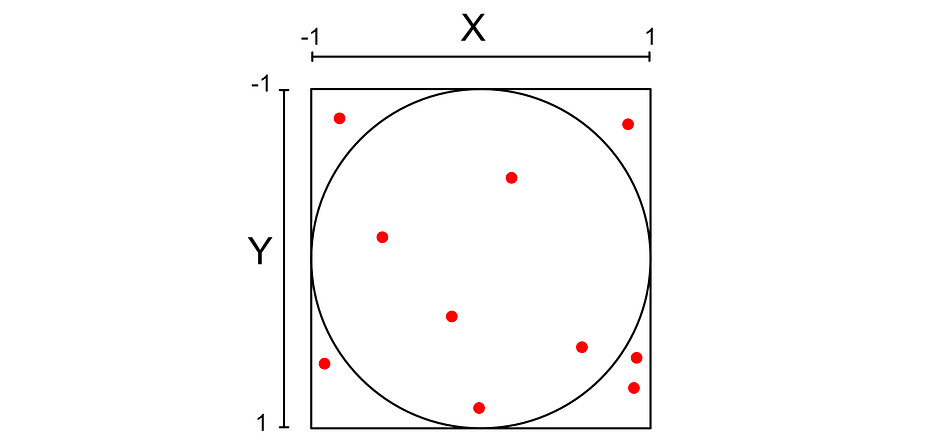

To do this, we’re going to use Monte Carlo estimation. Basically, we’ll stick a circle in a square and randomly place points within the square.

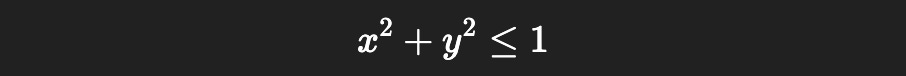

We can calculate if the point is inside the circle with the following expression.

I won’t get into the math, but the ratio of points in the circle should be approximately equal to pi over 4. If we had infinite points, this would be infinitely accurate.

We can do some algebra to move this expression around, to create an approximation for pi.

It’s crazy that Apple figured out those curved bezels before we calculated a decent approximation for pi, but I won’t try to think about it too hard. Let’s plan out how we might tackle this in K8s.

The Plan

If you read my article on Apache Spark, you might be familiar with the concept of “map-reduce,” which we’ll be using in this example.

We’re going to break this problem into two parts. First, we’ll define a worker that generates some number of random points in a cube, calculates if they are or are not within the square, and writes to a file how many of the points were in the circle, and how many points it tried. We’ll then build a simple “reducer” script, which takes in a few of those files and calculates digits of pi.

This separation is useful because we can employ more than one worker, who can work on the problem in parallel. Once the workers generate a bunch of points, the reducer can run when they finish, and reduce the results down into a single output.

We’ll be using k8s to manage how we’re orchestrating containers. To get started, let’s build the container itself.

Implementing the Worker and Reducer in Docker

To make things easy, we’re only going to specify one container, which holds both the worker and reducer logic. This will be the project’s file structure to start.

pi-estimator/

└─ src/

├─ worker.py

└─ reducer.pyOur worker.py file looks like this:

import os

import json

import random

import uuid

def estimate_chunk(num_points: int) -> tuple[int, int]:

“”“Simulate num_points Monte Carlo trials.

Returns (inside, total).”“”

inside = 0

for _ in range(num_points):

x = random.random() * 2 - 1 # Uniform in [-1, 1]

y = random.random() * 2 - 1

if x*x + y*y <= 1:

inside += 1

return inside, num_points

def main():

# How many points this worker should simulate

points_per_worker = int(os.environ.get(”POINTS_PER_WORKER”, “100000”))

# Where to write the result file

result_dir = os.environ.get(”RESULT_DIR”, “/results”)

# Make sure the directory exists

os.makedirs(result_dir, exist_ok=True)

# Perform the Monte Carlo trials

inside, total = estimate_chunk(points_per_worker)

# Generate a unique filename so workers don’t clash

result_file = os.path.join(result_dir, f”result-{uuid.uuid4()}.json”)

# Write out the result

with open(result_file, “w”) as f:

json.dump({”inside”: inside, “total”: total}, f)

print(f”[worker] Completed {total} points → inside={inside}”)

print(f”[worker] Wrote result to {result_file}”)

if __name__ == “__main__”:

main()We have a function estimate_chunk that does the actual work to generate random points and count which ones landed within the circle, and a main function that serves as an entry point and handles some key configuration details.

K8, which we’ll be using later, likes to communicate with containers via environment variables. As a result, we’re configuring how many points the script should test and where it should place the results, via environment variables.

reducer.py should look something like this:

import os

import json

def load_results(result_dir: str):

“”“Load all JSON result files from the directory.”“”

inside_total = 0

points_total = 0

if not os.path.exists(result_dir):

print(f”[reducer] Results directory not found: {result_dir}”)

return None, None

files = [f for f in os.listdir(result_dir) if f.endswith(”.json”)]

if not files:

print(”[reducer] No result files found. Did any workers run?”)

return None, None

for name in files:

file_path = os.path.join(result_dir, name)

try:

with open(file_path, “r”) as f:

data = json.load(f)

inside_total += data.get(”inside”, 0)

points_total += data.get(”total”, 0)

except Exception as e:

print(f”[reducer] Failed to read {file_path}: {e}”)

return inside_total, points_total

def compute_pi(inside: int, total: int) -> float:

“”“Compute the Monte Carlo estimate of pi.”“”

if total == 0:

return float(”nan”)

return 4 * inside / total

def main():

result_dir = os.environ.get(”RESULT_DIR”, “/results”)

print(f”[reducer] Collecting results from: {result_dir}”)

inside, total = load_results(result_dir)

if inside is None:

print(”[reducer] No valid data found. Exiting.”)

return

pi_estimate = compute_pi(inside, total)

print(f”[reducer] inside_total = {inside}”)

print(f”[reducer] points_total = {total}”)

print()

print(f”Distributed π estimate: {pi_estimate}”)

if __name__ == “__main__”:

main()It gets all the files in the output path, generated by all workers that have run, and computes pi. It also uses environment variables so the result directory can be configured externally.

We can make sure this works before we try to set up k8s around it. I’m going to define a script called local_test.py which runs this code using whatever version of Python comes in default in my Ubuntu virtual machine.

pi-estimator/

├─ local_test.py

└─ src/

├─ worker.py

└─ reducer.pyAnd here’s the actual implementation for local_test.py

import os

import json

import shutil

import subprocess

RESULT_DIR = “local_results”

def run_worker(points=100000):

“”“Run the worker.py script locally.”“”

print(f”[test] Running worker with {points} points...”)

env = os.environ.copy()

env[”POINTS_PER_WORKER”] = str(points)

env[”RESULT_DIR”] = RESULT_DIR

subprocess.run(

[”python”, “src/worker.py”],

env=env,

check=True

)

def run_reducer():

“”“Run the reducer.py script locally.”“”

print(f”[test] Running reducer...”)

env = os.environ.copy()

env[”RESULT_DIR”] = RESULT_DIR

subprocess.run(

[”python”, “src/reducer.py”],

env=env,

check=True

)

def reset_results():

“”“Clear out the results directory.”“”

if os.path.exists(RESULT_DIR):

shutil.rmtree(RESULT_DIR)

os.makedirs(RESULT_DIR, exist_ok=True)

def main():

print(”[test] Starting local Monte Carlo π estimation”)

reset_results()

# Run multiple workers

for i in range(3):

print(f”[test] Worker {i+1}/3”)

run_worker(points=200000)

print()

print(”[test] Running reducer to aggregate results:”)

print(”--------------------------------------------”)

run_reducer()

print(”--------------------------------------------”)

print(”[test] Done.”)

if __name__ == “__main__”:

main()Essentially, this script specifies environment variables and runs the worker a few times, then it runs the reducer. It’s not parallelized, but it does allow us to test the core logic and make sure everything is working correctly. When we run it, we get this output:

[test] Starting local Monte Carlo π estimation

[test] Worker 1/3

[test] Running worker with 200000 points...

[worker] Completed 200000 points → inside=157035

[worker] Wrote result to local_results/result-b6a69810-fe60-4f3d-bd2c-f4a29c80b249.json

[test] Worker 2/3

[test] Running worker with 200000 points...

[worker] Completed 200000 points → inside=156804

[worker] Wrote result to local_results/result-255f2b1b-01ce-467b-bc9d-135c06dd7758.json

[test] Worker 3/3

[test] Running worker with 200000 points...

[worker] Completed 200000 points → inside=156995

[worker] Wrote result to local_results/result-ba2466b4-04ec-4bc0-a866-b064b4b126d5.json

[test] Running reducer to aggregate results:

--------------------------------------------

[test] Running reducer...

[reducer] Collecting results from: local_results

[reducer] inside_total = 470834

[reducer] points_total = 600000

Distributed π estimate: 3.1388933333333333

--------------------------------------------

[test] Done.This runs great for a relatively small number of points, but if we increase the number of points past around a million, we quickly bump into significant slowdowns. Let’s Dockerize this and run it with K8s so we can get a few of these workers running in parallel.

Dockerizing Our Application

We’re going to create a Dockerfile outside of our source so we can dockerize the application.

pi-estimator/

├─ local_test.py

├─ Dockerfile

└─ src/

├─ worker.py

└─ reducer.py

└─ local_results/ <- automatically created by running local_test.py

├─ result-...json

├─ result-...json

└─ result-...jsonWe could implement two Docker containers, but to make things easier, we’ll be implementing one Docker container that contains both the worker and reducer code. Here’s the Dockerfile that will make that work.

FROM python:3.10-slim

WORKDIR /app

COPY src/worker.py src/reducer.py .

ENTRYPOINT [”python”]This is essentially the same as our Dockerfile from our previous example. It uses a base image, sets a working directory, and copies worker.py and reducer.py into that directory. The only difference is that, instead of specifying a command to run when the image is started up with CMD, we specify an ENTRYPOINT.

If we use CMD our docker container will run the same command every time. With ENTRYPOINT we can specify arguments when we actually run our docker image, which can modify how it’s run. When we run docker run my_image <arg1> <arg2>, it will be appended to whatever as specified in the ENTRYPOINT. In this case, that would be python <arg1> <arg2>. Thus, when we start up an image, we can specify if it’s a worker or reducer simply by changing the arguments we set when we run the image, via something like docker run my_image worker.py or docker run my_image reducer.py.

We can build this Docker container by navigating into the pi-estimator directory and running

sudo docker build -t pi-estimator .We can make sure everything works by running the Docker file all by itself. Recall that the worker requires some environment variables to be properly configured, and then will output a JSON file to a directory. We’re going to run the image, specify that it’s a worker, and set up the configuration and output path all within one command:

sudo docker run --rm \

-e POINTS_PER_WORKER=200000 \

-e RESULT_DIR=/results \

-v $(pwd)/local_results:/results \

pi-estimator worker.pyThere’s four core things going on. First, this means we’re running a Docker image and killing it when it’s done.

sudo docker run --rm-e allows us to set environment variables. We’re setting two, one is how many points the worker generates, and the other is the output directory. These are compatible with what we set up in worker.py

-e POINTS_PER_WORKER=200000 \

-e RESULT_DIR=/results \This is kind of a tricky one. Recall that docker containers have their own file system, which isolates them from the host system they’re running on. That’s great, but it would mean we can’t actually see our results, because they’ll be deleted when the image stops executing. To alleviate that, we’re going to attach a volume ( -v ) which allows us to specify a file from our computer’s file system that will be mounted to Docker. When Docker writes to that folder, it will be written to the folder on the host machine.

-v $(pwd)/local_results:/resultsThe syntax is -v local_path:path_in_docker, so we’re mounting local_results in our file system into our container as the results directory. Recall that we set the environment variable -e RESULT_DIR=/results in the previous step, so the Docker container will write its results to this folder, which means it will write its results to our computer.

The final line is the actual Docker container we’ll be running, and the argument that will be tacked onto the ENTRYPOINT

pi-estimator worker.pySo, within our container, we’ll be running python worker.py.

Running that whole command results in this output

[worker] Completed 200000 points → inside=157024

[worker] Wrote result to /results/result-89f2d5d5-3b62-441b-a075-cc62baad0a10.jsonand, if we look into our local_results directory, we’ll see a new json file was created. We can run this command a few more times if we want, then run this to execute our reducer

sudo docker run --rm \

-e RESULT_DIR=/results \

-v $(pwd)/local_results:/results \

pi-estimator reducer.pywhich, for me, outputs this:

reducer] Collecting results from: /results

[reducer] inside_total = 785219

[reducer] points_total = 1000000

Distributed π estimate: 3.140876Alright, we’ve containerized our application. It’ll work pretty much the same on any operating system, and we can spool it up with a single command to Docker. Let’s automate the orchestration and parallelization of these containers with Kubernetes.

A Brief Interlude, The Anatomy of Kubernetes

I typically avoid jargon as much as possible, but with K8s it’s hard to avoid. Before we move on I’d like to cover some basic Kubernetes ideas. These are the core elements that make up most K8s clusters. Feel free to refer back to this section if you’re confused about specific names. We’ll be using some of these words later in the article.

Clusters: The whole idea of K8s is that it allows you to run a job across multiple computers. Those computers, together, form a cluster.

Node: Each individual computer within the cluster

Pod: The smallest runnable unit in K8s. Kubernetes manages the creation and deletion of pods, which contain containers and run within a node. Usually, a Pod only contains a single container, but in some more advanced applications, a few containers can exist within a single pod. You can think of a “pod” as a scheduled unit in K8s, usually corresponding to a single container.

Container: We’ve covered this in depth. It’s a container, like Docker. There are more containerization technologies, like Podman, but Docker is the most common.

Volume: This is persistent storage mounted onto a Pod, which that Pod’s containers can access and use. If there’s a failure and a pod needs to restart, this allows the data to persist. Also, if more than one Pod in a container needs to talk with one another, we can do that by having them share files.

Persistent Volume: Unlike a normal volume (which lives only as long as its Pod), a PersistentVolume exists independently from any Pod that uses it. It’s used for databases, queues, things like that.

Service: Basically, networking for a pod. Different services expose Pods in different ways. For instance, you can assign an IP address to your Pod, so that Pods within a cluster can communicate with each other over HTTP requests. You can also employ load balancers, which can balance incoming requests from external sources and distribute them to various nodes in the cluster.

Ingress: This allows you to route incoming requests to different services, and thus to different pods. For instance, you might have a pod that manages login, and a pod that manages core application logic. When your K8s cluster gets a request for

example.com/login, it can route that request to the service that corresponds to the pod for login. In other words, Ingress allows you to set rules as to how requests are routed throughout the pods in your cluster.Controller: A controller is a background process inside Kubernetes that constantly compares the actual state of the cluster with the desired state, and takes action to make them match. In K8s you declare what you want with something called a “manifest”, then k8s uses controllers to try to make what you want.

Replica Set: Ensures that a certain number of identical Pods are always running. If a Pod crashes or a node dies, the ReplicaSet creates a new one, keeping your pods alive through failure. This is usually managed by the controller, not the user.

The Control Plane: The control plane is the brains of kubernetes. It contains the controller manager (which actually runs the controller), the API server (which manages all traffic into and out of the cluster, including communication to manage the cluster itself), the scheduler (which observes resource usage in pods, obeys specified constraints, and allocates pods to certain nodes as necessary), and etcd (which serves as memory for the control plane).

Kubelet: Runs on each node, receives instructions from the control plane, and manages the running of pods. This is managed by K8s.

Namespace: A way to organize and isolate resources inside a cluster by assigning them by name. Resources in one namespace don’t conflict with resources in another, allowing you to spool up several parallel versions of an application within a single cluster. This is commonly used to separate dev/staging/prod or to give teams their own space.

ConfigMap and Secret: We won’t be touching on these a lot in this tutorial, but they’re super important when building actual applications in the real world. Many K8s use cases involve complex environment variables that might be sensitive (like API keys) or require sophisticated workflows around setting them (like CICD). ConfigMaps and Secrets are special ways of dealing with environment variables that make them modular and more secure.

Orchestrating with Kubernetes

We’re going to make a new folder in our folder structure called k8s , which will contain a file called pi-job.yaml. This will specify how we configure kubernetes to run our application. We’re also creating a helper file called pi-image-structure.yaml, which we’ll discuss later.

pi-estimator/

├─ local_test.py

├─ Dockerfile

└─ k8s/

├─ pi-job.yaml

└─ pi-image-structure.yaml

└─ src/

├─ worker.py

└─ reducer.py

└─ local_results/

└─ ....jsonpi-job.yaml is the major file that tells K8s what to do. We’ll go through line by line, but here’s the whole file:

# -------------------------------------------------------

# Persistent Volume Claim (shared across workers & reducer)

# -------------------------------------------------------

apiVersion: v1

kind: PersistentVolumeClaim

metadata:

name: pi-results-pvc

spec:

accessModes:

- ReadWriteMany

resources:

requests:

storage: 1Gi

---

# =======================================================

# RBAC so reducer can check worker pod status

# =======================================================

apiVersion: v1

kind: ServiceAccount

metadata:

name: pi-reducer-sa

---

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: Role

metadata:

name: pi-reducer-role

rules:

- apiGroups: [”“]

resources: [”pods”]

verbs: [”get”, “list”]

- apiGroups: [”batch”]

resources: [”jobs”]

verbs: [”get”, “list”]

---

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: RoleBinding

metadata:

name: pi-reducer-binding

subjects:

- kind: ServiceAccount

name: pi-reducer-sa

roleRef:

kind: Role

name: pi-reducer-role

apiGroup: rbac.authorization.k8s.io

---

# -------------------------------------------------------

# Worker Job (4 Pods in parallel)

# -------------------------------------------------------

apiVersion: batch/v1

kind: Job

metadata:

name: pi-workers

spec:

completions: 4

parallelism: 4

backoffLimit: 0

template:

spec:

restartPolicy: Never

containers:

- name: worker

image: pi-estimator

imagePullPolicy: Never

command: [”python”, “/app/worker.py”]

env:

- name: POINTS_PER_WORKER

value: “200000”

- name: RESULT_DIR

value: “/results”

volumeMounts:

- name: results

mountPath: /results

volumes:

- name: results

persistentVolumeClaim:

claimName: pi-results-pvc

---

# -------------------------------------------------------

# Reducer Job (waits for all 4 workers to finish)

# -------------------------------------------------------

apiVersion: batch/v1

kind: Job

metadata:

name: pi-reducer

spec:

completions: 1

parallelism: 1

backoffLimit: 0

template:

spec:

restartPolicy: Never

serviceAccountName: pi-reducer-sa

initContainers:

- name: wait-for-workers

image: bitnami/kubectl:latest

command:

- sh

- -c

- |

echo “[init] Waiting for 4 worker pods to complete...”

while true; do

succ=$(kubectl get pods -l job-name=pi-workers \

--field-selector=status.phase=Succeeded \

--no-headers | wc -l)

echo “[init] Workers finished: ${succ}/4”

if [ “$succ” -ge 4 ]; then

echo “[init] All workers completed, starting reducer.”

break

fi

sleep 2

done

containers:

- name: reducer

image: pi-estimator

imagePullPolicy: Never

command: [”python”, “/app/reducer.py”]

env:

- name: RESULT_DIR

value: “/results”

volumeMounts:

- name: results

mountPath: /results

volumes:

- name: results

persistentVolumeClaim:

claimName: pi-results-pvcThis is called a Kubernetes manifest file, which declares what we want Kubernetes to create and manage for us. It’s organized into six resource manifests:

One for a persistent volume (so different processes can send data to one another)

Three to set the correct permissions (we’ll talk about these later)

One to kick off four of the workers, which run in parallel

One to kick off the reducer, which aggregates the output from each of the workers and returns a prediction for pi.

Each of these manifests starts with an apiVersion, something like this:

apiVersion: batch/v1Originally, Kubernetes only had one apiVersion, which was v1. This contains the core elements of Kubernetes. As Kubernetes evolved and became more popular, different types of use cases became more prevalent. People were using Kubernetes to run large computational jobs, and people were using Kubernetes to support long-lasting applications. To support these types of workflows, the batch/v1 and apps/v1 APIs were created to run ephemeral jobs and long-lived applications, respectively. v1, apps/v1, and batch/v1 cover the vast majority of Kubernetes, though there are many other APIs that are important for some specific functionality.

on top of the API version, each resource also has a kind, which specifies the kind of resource we want to make within the apiVersion we’re using. Exactly what a kind represents can change depending on the apiVersion we’re using. For instance, it might represent what type of batch operation we’re making

apiVersion: batch/v1

kind: Job

...it might represent that we want a persistent volume

apiVersion: v1

kind: PersistentVolumeClaim

...Or that we want to create roles and bind those roles to resources.

apiVersion: v1

kind: ServiceAccount

...

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: Role

...

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: RoleBindingThere’s a lot going on in this manifest file, chiefly because we need a few different resources to get everything working. We can pick this apart by understanding each resource individually and what it’s doing. The simplest one is probably the persistent volume.

# -------------------------------------------------------

# Persistent Volume Claim (shared across workers & reducer)

# -------------------------------------------------------

apiVersion: v1

kind: PersistentVolumeClaim

metadata:

name: pi-results-pvc

spec:

accessModes:

- ReadWriteMany

resources:

requests:

storage: 1GiEach resource manifest consists of four key parts; the apiVersion and kind, which we discussed and will continue to explore, and the metadata and spec.

The metadata field allows you to assign information that’s useful to both humans and Kubernetes in terms of organization and grouping of resources. For this example we’re keeping it simple and just assigning a name which is pi-results-pvc (the persistent volume claim for the results of our pi-finding workers). Setting a name is important because it’s common to control and interact with resources by name in K8s. This will be super important in both the examples in this article.

The spec is where all the magic happens; it’s where you define what you actually want out of the resource. The most important for a persistent volume claim ( pvc ) is the request for some volume of storage.

resources:

requests:

storage: 1GiWhen you create a persistent volume claim and pass it to K8s, K8s then

passes that request to the control plane in your cluster. Depending on

whether your Kubernetes is running locally using Minikube or on a cloud

provider like AWS, GCP, or Azure, different storage provisioners are used

to fulfill that request. It’s important to note here that manifests are “declarative”, meaning they declare the state we want to achieve. If an existing PersistentVolume already satisfies the claim, the control-plane controllers will bind the PVC to it.

On top of the amount of storage, we’re also defining the access modes.

spec:

accessModes:

- ReadWriteMany

resources:

requests:

storage: 1GiThis says that we want to allow many different pods (essentially, different instances of containers) to be able to read and write to this volume simultaneously. There are a few different approaches that can be useful in different use cases.

ReadWriteOnce: One machine can write to it, and any pods on that machine can use it.

ReadWriteOncePod: Only a single pod is allowed to write to it, even if multiple pods are on the same machine.

ReadOnlyMany: Many pods on many machines can use it, but only for reading.

ReadWriteMany: Many pods on many machines can use it and write to it at the same time.

ReadWriteMany can result in race conditions and conflicts, so it’s not good for every use case, but for this application it should work fine; our worker nodes run in isolation, and our reducer will only read once all workers are done running.

Now that we have a claim for volume, let’s discuss the worker job, which uses that volume.

# -------------------------------------------------------

# Worker Job (4 Pods in parallel)

# -------------------------------------------------------

apiVersion: batch/v1

kind: Job

metadata:

name: pi-workers

spec:

completions: 4

parallelism: 4

backoffLimit: 0

template:

spec:

restartPolicy: Never

containers:

- name: worker

image: pi-estimator

imagePullPolicy: Never

command: [”python”, “/app/worker.py”]

env:

- name: POINTS_PER_WORKER

value: “200000”

- name: RESULT_DIR

value: “/results”

volumeMounts:

- name: results

mountPath: /results

volumes:

- name: results

persistentVolumeClaim:

claimName: pi-results-pvcRecall that, in our original Docker container, we defined two scripts; worker.py could be used to generate a bunch of points and say if they’re inside or outside of a circle, then reducer.py could take those results (written as a json file) to calculate pi. Here, we’re defining a Job which spawns four workers and runs them in parallel.

Recall, there are three important core APIs in K8s, the v1 , app/v1, and batch/v1 apis. From a high-level view, the batch api has controllers for managing finite and scheduled tasks, while the app api has controllers for managing long-running applications. These are the most critical ones:

batch/v1: Job— A controller for executing on a specific task, then tears everything down when done. Good if you want to press play, execute a job, then free up resources when it’s done.batch/v1: CronJob— Similar to jobs, tares down on completion, but the controller sticks around so it can restart the task on a schedule. Good if you want to run a job every hour/day/week/etc.app/v1: Deployment— Runs long-lived applications and stateless applications. Probably the most important type of controller in K8s. Think the resources necessary to run a standard website.app/v1: StatefulSet— Similar to Deployment, but with extra rules imposed to enforce statefulness.app/v1: DaemonSet— Runs something on every machine (node) in the cluster. Useful for things like logging and monitoring.

A batch/v1: Job, then, is perfect for our application. We want the job to run, then stop running. Within this Job we’re assigning a name of pi-workers in the metadata field then defining a spec.

The spec has a few high-level parameters

spec:

completions: 4

parallelism: 4

backoffLimit: 0This says we want to spawn pods (containers) until four of them complete successfully, and we want to run four of them in parallel. K8s is designed to be resilient to error, so it will automatically retry running containers if they fail. This allows us to stop once we’ve run a certain amount successfully. By default, K8s will keep trying indefinitely, but we also set backoffLimit to zero, meaning K8s won’t retry running a pod that’s failed. This isn’t strictly required, but it means if we accidentally introduce a bug K8s won’t try to keep launching the same container over and over again.

After those simple configurations, we have the template for the worker itself

spec:

completions: 4

parallelism: 4

backoffLimit: 0

template:

spec:

restartPolicy: Never

containers:

- name: worker

image: pi-estimator

imagePullPolicy: Never

command: [”python”, “/app/worker.py”]

env:

- name: POINTS_PER_WORKER

value: “200000”

- name: RESULT_DIR

value: “/results”

volumeMounts:

- name: results

mountPath: /results

volumes:

- name: results

persistentVolumeClaim:

claimName: pi-results-pvcNow that we’ve covered some definitions and core ideas, this is pretty straightforward to understand. Each of the four pods this Job is spawning consists of a single container with an image named pi-estimator, which is the name of the Docker image we made. We’re starting that container with the command python /app/worker.py, which runs our worker script once the container starts.

We’re also specifying a few environment variables within the env clause, allowing us to specify how many points each worker simulates, and where the results end up.

We’re setting the RESULT_DIR environment variable to the same path we’re mounting the persistent volume to, meaning after our script runs, each of our workers will write its own output file to the persistent volume, allowing us to aggregate our results in a single place.

There’s two other fields that aren’t strictly necessary, but made their way in through the debugging process. imagePullPolicy: Never means we’ll never pull the image from an external registry, like Docker Hub, and restartPolicy: Never means if the pod fails, never restart it. This is common for a Job because it needs pods to conclude to be able to manage the pods correctly. If the pod keeps restarting itself every time it finishes, then the pod never concludes, and the Job can’t be managed properly.

The astute among you might notice that we’re calling /app/worker.py. Our Dockerfile which defines our image looks like this

FROM python:3.10-slim

WORKDIR /app

COPY src/worker.py src/reducer.py .

ENTRYPOINT [”python”]It can be kind of hard to be 100% sure where all our files are within the docker container. Instead of guessing, I made a simple manifest file that lets us explore the folder structure of our image, called pi-image-structure.yaml.

apiVersion: batch/v1

kind: Job

metadata:

name: pi-image-structure

spec:

backoffLimit: 0

template:

spec:

restartPolicy: Never

containers:

- name: explorer

image: pi-estimator:latest

imagePullPolicy: Never

command: [”/bin/sh”, “-c”]

args:

- |

echo “=== DIRECTORY LISTING OF /app (detailed) ===”;

ls -alh /app;

echo;

echo “=== RECURSIVE LISTING OF /app ===”;

ls -R /app;

echo;

echo “=== TREE VIEW OF /app (manual) ===”;

find /app -printf “%p\n”;

echo “=== DONE ===”;It’s just like the Job we were just talking about, except it only spawns the image once, and instead of running a command to run our script, it runs some commands to view the structure of the files within the image. I don’t want this tangent to take too long, we haven’t finished discussing the big manifest file running our job. It’s just a little hack I used to make sure all of my paths were set up correctly.

Anyway, back to our manifest file for our pi estimation. We discussed two of the resources so far; the persistent volume claim and the parallel job for the workers. We also need another Job which runs the reducer after the workers are done. This resource manifest makes that happen.

# -------------------------------------------------------

# Reducer Job (waits for all 4 workers to finish)

# -------------------------------------------------------

apiVersion: batch/v1

kind: Job

metadata:

name: pi-reducer

spec:

completions: 1

parallelism: 1

backoffLimit: 0

template:

spec:

restartPolicy: Never

serviceAccountName: pi-reducer-sa

initContainers:

- name: wait-for-workers

image: bitnami/kubectl:latest

command:

- sh

- -c

- |

echo “[init] Waiting for 4 worker pods to complete...”

while true; do

succ=$(kubectl get pods -l job-name=pi-workers \

--field-selector=status.phase=Succeeded \

--no-headers | wc -l)

echo “[init] Workers finished: ${succ}/4”

if [ “$succ” -ge 4 ]; then

echo “[init] All workers completed, starting reducer.”

break

fi

sleep 2

done

containers:

- name: reducer

image: pi-estimator

imagePullPolicy: Never

command: [”python”, “/app/reducer.py”]

env:

- name: RESULT_DIR

value: “/results”

volumeMounts:

- name: results

mountPath: /results

volumes:

- name: results

persistentVolumeClaim:

claimName: pi-results-pvcThis is virtually the same as the worker manifest, save two key differences. First and most trivially, it calls the reducer.py script, rather than the worker.py script. It also uses an initContainer.

When you run a manifest file in K8s, it creates all resources at the same time asynchronously. That means K8s will create our worker job with 4 workers (which take a while to run because they have a lot of work to do) and our reducer at the same time. If we run our reducer as soon as it’s spooled up, it will look in the shared volume and see that there’s nothing in there, as the workers haven’t finished running yet.

There are a few ways of dealing with this, which have their costs and benefits. I opted to use something called an initContainer. initContainers run before your actual container, in order if you have more than one init container. Your actual container in your pod only runs after all of your init containers have finished running. Thus, if we make our initContainer run as long as we have workers running, then it will effectively delay our reducer from starting until after all of our workers have finished.

This is the definition for the initContainer

initContainers:

- name: wait-for-workers

image: bitnami/kubectl:latest

command:

- sh

- -c

- |

echo “[init] Waiting for 4 worker pods to complete...”

while true; do

succ=$(kubectl get pods -l job-name=pi-workers \

--field-selector=status.phase=Succeeded \

--no-headers | wc -l)

echo “[init] Workers finished: ${succ}/4”

if [ “$succ” -ge 4 ]; then

echo “[init] All workers completed, starting reducer.”

break

fi

sleep 2

doneIt uses a base image called bitnami/kubectl:latest which is a very popular kubernetes image designed to run kubectl commands from within a container. This lets it spool up an image that can talk with the cluster it’s in.

The command we’re sending to this image is formatted a bit weirdly, simply because it’s a Yaml file. The YAML file expects a list of commands, so a YAML file like this:

command:

- thing1

- thing2

- thing3would look like a command like

thing1 thing2 thing3The symbol | is a convention in YAML which means “treat the following thing as a single multi-lined string, line breaks and all. So we’re essentially running the command:

sh -c “

echo \”[init] Waiting for 4 worker pods to complete...\”

while true; do

succ=\$(kubectl get pods -l job-name=pi-workers \

--field-selector=status.phase=Succeeded \

--no-headers | wc -l)

echo \”[init] Workers finished: \${succ}/4\”

if [ \”\$succ\” -ge 4 ]; then

echo \”[init] All workers completed, starting reducer.\”

break

fi

sleep 2

done

“the command sh specifies that we’re simply running a command in the Unix POSIX shell, which every Linux machine has. the -c argument says “run the following string as a command”, then we’re passing the string into it, which is written in POSIX shell script. If you’re not familiar with POSIX shell scripts this might look a bit daunting. In essence:

It prints the text

[init] Waiting for 4 worker pods to complete…while true; dostarts an infinite loop which will always run until broken out ofsucc=…counts the number of completed worker pods. It does that by getting all the pods withkubectl get podswith a filter that only selects pods of the correct name with-l job-name=pi-workersand only keeps pods that have successfully finished with— field-selector=status.phase=Succeeded. It makes sure there are no headers with— no-headers, and| wc -lcounts how many lines exist within the resulting text from the previous commands. Basically, we’re making a line of text for all of the workers that have finished successfully, and are counting the number of rows.If the number of successful pods is greater than or equal to four

if [ \”\$succ\” -ge 4 ]; then, then print and break out. Otherwise sleep for two seconds.

I think it’s kind of cool how we didn’t need to implement any code. By using a base image that already had kubectl set up, we could just use a kubectl and some fancy shell scripting to whip up some sophisticated functionality. The end result is that our init container doesn’t stop running until all workers have stopped running. It also consumes practically zero resources, as the Docker image is lightweight and the majority of time the image is sleeping (thus not consuming resources).

By default, a pod can’t run kubectl commands to be able to communicate with the cluster it exists within, as a matter of security. To enable these permissions, we specify serviceAccountName: pi-reducer-sa, which is another set of resources we need to define in our manifest.

apiVersion: v1

kind: ServiceAccount

metadata:

name: pi-reducer-sa

---

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: Role

metadata:

name: pi-reducer-role

rules:

- apiGroups: [”“]

resources: [”pods”]

verbs: [”get”, “list”]

- apiGroups: [”batch”]

resources: [”jobs”]

verbs: [”get”, “list”]

---

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: RoleBinding

metadata:

name: pi-reducer-binding

subjects:

- kind: ServiceAccount

name: pi-reducer-sa

roleRef:

kind: Role

name: pi-reducer-role

apiGroup: rbac.authorization.k8s.ioFirst, we create a service account, which pods can use as an identity when talking with the Kubernetes API in the control plane.

apiVersion: v1

kind: ServiceAccount

metadata:

name: pi-reducer-saNext, we define a role, which defines a set of actions that an account would be able to perform. This allows for getting (reading one) and listing (reading all) pods and jobs.

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: Role

metadata:

name: pi-reducer-role

rules:

- apiGroups: [”“]

resources: [”pods”]

verbs: [”get”, “list”]

- apiGroups: [”batch”]

resources: [”jobs”]

verbs: [”get”, “list”]We then bind that role to the service account, by specifying the service account and role by name within a RoleBinding.

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: RoleBinding

metadata:

name: pi-reducer-binding

subjects:

- kind: ServiceAccount

name: pi-reducer-sa

roleRef:

kind: Role

name: pi-reducer-role

apiGroup: rbac.authorization.k8s.ioA bit verbose, and some boilerplate, but conceptually intuitive I think.

And that’s actually all we need to code up to get our container working in kubernetes. Lets spool up minikube and run it.

Running in Kubernetes

First of all, we defined a lot of stuff in the last section, and it’s probably a good idea to do a simple smoke test. We have two manifest files in our k8s folder; pi-job.yaml which is super complicated, and pi-image-structure.yaml which simply prints out the directory structure within our image. Let’s try running pi-image-structure.yaml first, to make sure everything is set up nicely.

pi-estimator/

├─ local_test.py

├─ Dockerfile

└─ k8s/

├─ pi-job.yaml

└─ pi-image-structure.yaml

└─ src/

├─ worker.py

└─ reducer.py

└─ local_results/

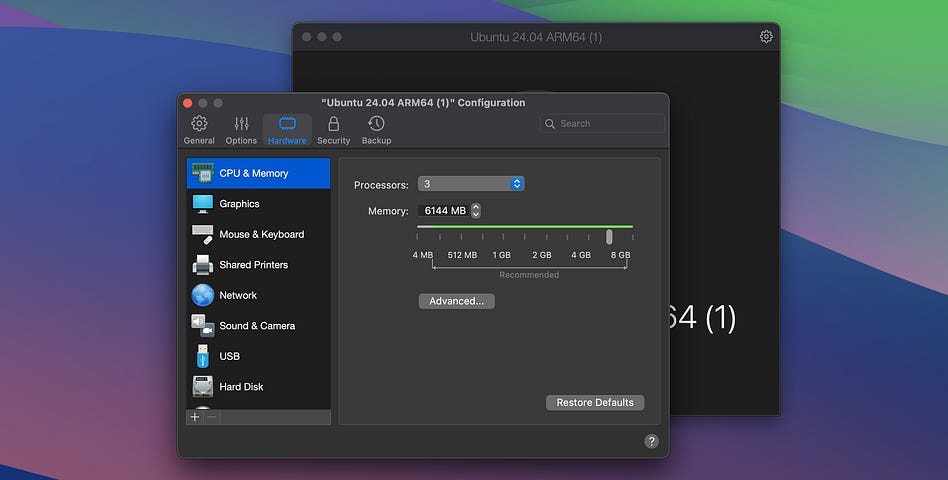

└─ ....jsonFirst of all, recall I’m running all this in a virtual machine. If you’re doing something similar, I recommend allocating plenty of RAM in the VM so Kubernetes doesn’t have any issues.

On Parallels, you can do that by making sure the VM is shut down, opening it by double-clicking the name, and clicking the gear on the top right. You can then give it a good amount of processors and RAM to play with.

Once you do that, go ahead and start up the VM.

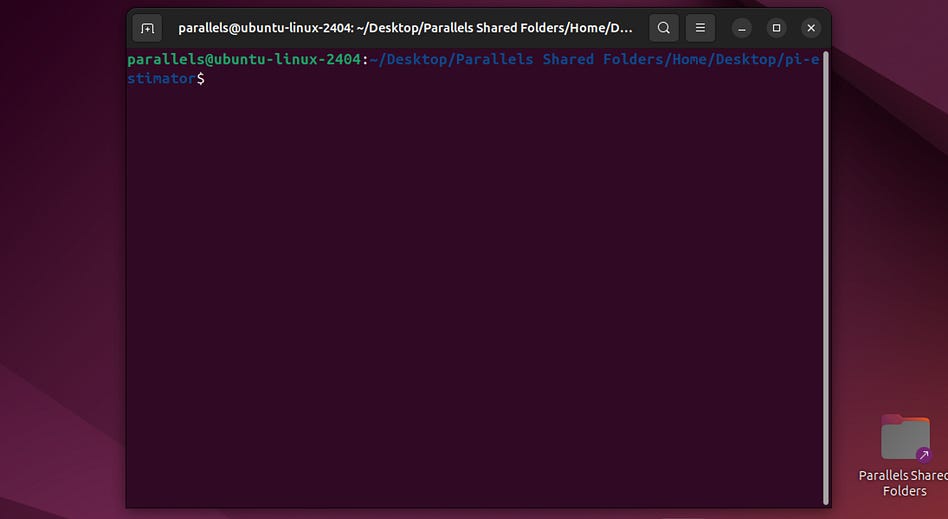

Open up a terminal, and CD into wherever your pi-estimator directory is

then run

minikube startYou’ll get a bunch of emojis and a message saying minikube started. Then run

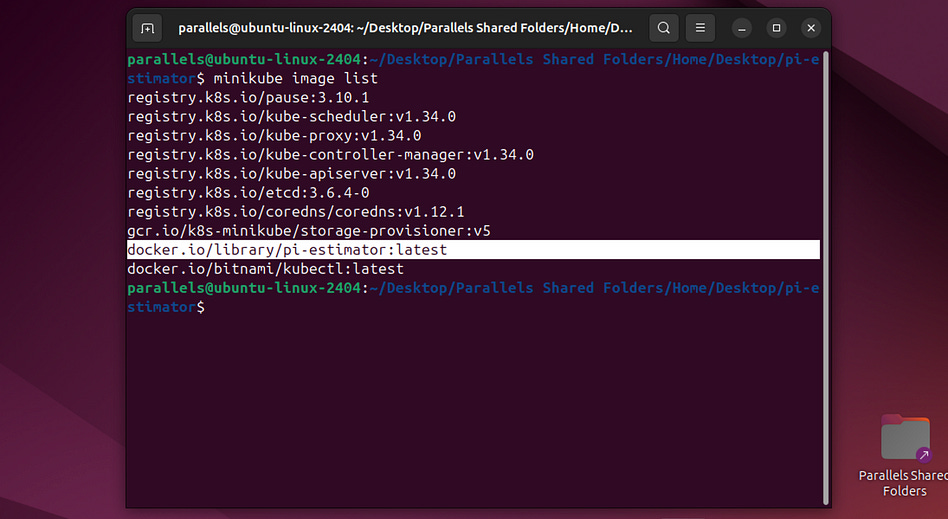

minikube image build -t pi-estimator:latest .This will build the docker image for pi-estimator, based on our Dockerfile, and load it into minikube. if we then run

minikube image listwe’ll be able to see our image in minikube.

Let’s go ahead and cd into our k8s folder, and run

kubectl apply -f pi-image-strcture.yamlwhich should return something like this.

job.batch/pi-image-structure createdRecall that pi-image-structure.yaml defines a simple command that prints out the directory structure of our pi-estimator docker image. Running kubectl apply applies this manifest to the cluster.

We can then run the following command to see that our job ran and completed.

kubectl get jobsNAME STATUS COMPLETIONS DURATION AGE

pi-image-structure Complete 1/1 4s 59sWe can also run the following commands to see the individual pod which was created during the job, ran successfully, then destroyed.

kubectl get podsNAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

pi-image-structure-rmgh2 0/1 Completed 0 2m52sWe can run the following command to check out the logs from all pods that ran in this job (only the one)

kubectl logs -l job-name=pi-image-structure --prefix[pod/pi-image-structure-rmgh2/explorer] === RECURSIVE LISTING OF /app ===

[pod/pi-image-structure-rmgh2/explorer] /app:

[pod/pi-image-structure-rmgh2/explorer] reducer.py

[pod/pi-image-structure-rmgh2/explorer] worker.py

[pod/pi-image-structure-rmgh2/explorer]

[pod/pi-image-structure-rmgh2/explorer] === TREE VIEW OF /app (manual) ===

[pod/pi-image-structure-rmgh2/explorer] /app

[pod/pi-image-structure-rmgh2/explorer] /app/worker.py

[pod/pi-image-structure-rmgh2/explorer] /app/reducer.py

[pod/pi-image-structure-rmgh2/explorer] === DONE ===And we can see that the /app directory contains our worker.py and our reducer.py. More importantly, though, we just successfully ran our first Kubernetes manifest!

Of course, our actual pi-job.yaml is way more complicated, but running it is pretty much the same thing. First, though, let’s run this command to delete all traces of our pi-image-structure so it’s not polluting our output.

kubectl delete job pi-image-structureThese two commands should both result in an empty output

kubectl get jobs

kubectl get podsWe can now run

kubectl apply -f pi-job.yamland see that a bunch of resources were created (or unchanged, because I ran this previously)

persistentvolumeclaim/pi-results-pvc created

serviceaccount/pi-reducer-sa unchanged

role.rbac.authorization.k8s.io/pi-reducer-role unchanged

rolebinding.rbac.authorization.k8s.io/pi-reducer-binding unchanged

job.batch/pi-workers created

job.batch/pi-reducer createdAnd we have a bunch of pods that all finished pretty quickly.

kubectl get podsNAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

pi-reducer-zwxnb 0/1 Completed 0 5s

pi-workers-784w4 0/1 Completed 0 5s

pi-workers-sq2q5 0/1 Completed 0 5s

pi-workers-x9nnl 0/1 Completed 0 5s

pi-workers-z6znv 0/1 Completed 0 5sWe can view the logs across all our workers

kubectl logs -l job-name=pi-workers --prefix[pod/pi-workers-784w4/worker] [worker] Completed 200000 points → inside=157207

[pod/pi-workers-784w4/worker] [worker] Wrote result to /results/result-3ae62882-d551-4e5d-b5df-5f7c3b2124a6.json

[pod/pi-workers-sq2q5/worker] [worker] Completed 200000 points → inside=157099

[pod/pi-workers-sq2q5/worker] [worker] Wrote result to /results/result-e4094053-03b7-477d-a80d-d0f97b8e7cbc.json

[pod/pi-workers-x9nnl/worker] [worker] Completed 200000 points → inside=157433

[pod/pi-workers-x9nnl/worker] [worker] Wrote result to /results/result-b715483c-5845-4f28-9258-ff09a20d030e.json

[pod/pi-workers-z6znv/worker] [worker] Completed 200000 points → inside=157704

[pod/pi-workers-z6znv/worker] [worker] Wrote result to /results/result-d31f9b4a-daf4-43e0-a792-f62b7eb5e916.jsonand the logs in our reducer

kubectl logs -f job/pi-reducerDefaulted container “reducer” out of: reducer, wait-for-workers (init)

[reducer] Collecting results from: /results

[reducer] inside_total = 314786221

[reducer] points_total = 400800000

Distributed π estimate: 3.1415790518962075And see that it successfully aggregated all of the results from our workers! We could scale up the number of points, scale up the number of workers, and waste a whole lot of money on AWS if we really wanted to.

This is pretty nifty, but you might notice a key issue. Everything is hard-coded. If we wanted to increase the number of workers or how many points each worker was processing, we’d need to manually adjust our manifest file. This is possible, and it might even be acceptable in some applications, but it feels like this particular problem needs some ease of configuration. We can do that with Helm.

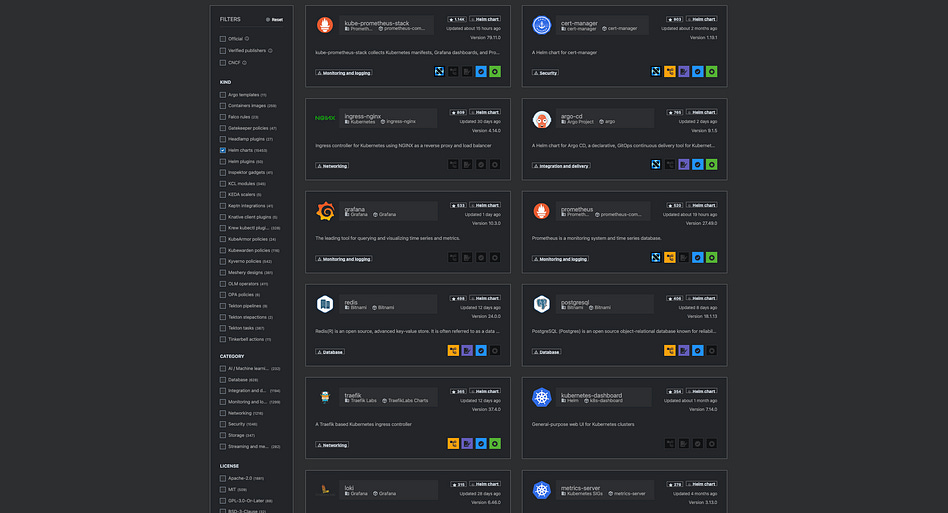

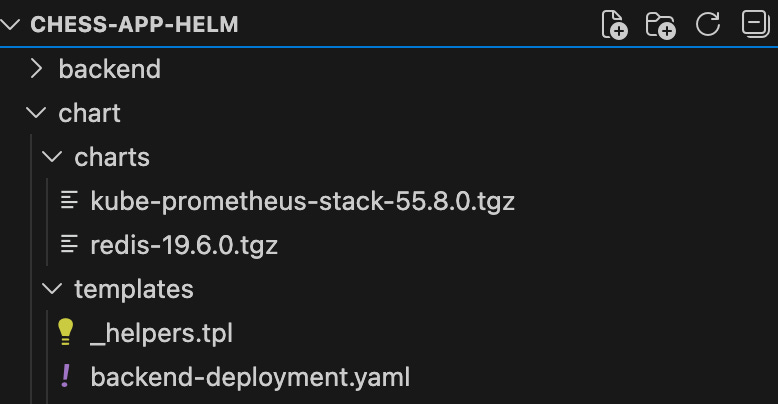

Helm

Helm is often described as “the package manager for Kubernetes”; it abstracts Kubernetes into something called a chart, which allows you to connect different Kubernetes applications together like Legos. We’ll play around with that later. For now, we’ll be using a functionality of Helm called templating to be able to configure our Job before running it.

We can kick off working in helm by navigating to pi-estimator and running

helm create chartThis creates a directory in pi-estimator called chart, which will contain a bunch of boilerplate we don’t need. We can clean it up with the following:

rm -rf chart/templates/*

rm -rf chart/templates/tests

rm -f chart/values.yaml

touch chart/values.yamlThis will clean up a bunch of the default stuff we don’t need, and make a barebones basis for us to work off of. Something like this:

pi-estimator/

chart/

Chart.yaml

values.yaml

templates/

...

k8s/

...

src/

...

...Helm relies on two core ideas to do it’s magic, the chart and templates. A chart is essentially a package that contains everything necessary to define a K8s application. It has metadata about it, which is defined in Chart.yaml, default configuration values defined in values.yaml and configurable templates defined in the templates directory.

Instead of defining our K8s application in one big manifest, we break up all the resources into different templates. Each of these templates can have variables, which can have default values defined in values.yaml or can be manually changed. This is what will allow us to run our pi estimation job with a varying number of workers, a varying number of points per worker, and other fun stuff like that.

To get started, we can go into Chart.yaml and define it as

apiVersion: v2

name: pi-estimator

description: A Helm chart for running a parallel Pi estimation job in Kubernetes.

type: application

version: 0.1.0

appVersion: “1.0”This defines the v2 API for Helm, which is the current standard, and the name of the application is pi-estimator. We give it a description, and assign it as type: application (as opposed to the alternative type: library, which isn’t designed to be run on its own but instead consists of re-usable logic). There’s also some versioning information, which can be useful if you’re trying to keep track of logic around the helm chart or application as a whole. When we later call helm install pi-estimator ./chart, helm will look for our Chart.yaml file in the directory, and will look for a template directory, that contains our resource definitions.

Within our template directory we need one template for each of our resources. Behind the scenes, Helm will compile these into a single manifest. This will look a lot like our pi-job.yaml from Kubernetes, with one minor change: variables. Here’s an example of a template for our persistent volume claim.

apiVersion: v1

kind: PersistentVolumeClaim

metadata:

name: {{ .Values.pvc.name }}

spec:

accessModes:

- {{ .Values.pvc.accessMode }}

resources:

requests:

storage: {{ .Values.pvc.size }}If you scroll back through our k8s manifest file, you’ll see this is exactly the same, except some of the fields are abstracted away into variables surrounded by double curly brackets. This would be saved in templates/pvc.yaml, and all of the other resources would get their own templace, like so.

templates/pvc.yaml

apiVersion: v1

kind: PersistentVolumeClaim

metadata:

name: {{ .Values.pvc.name }}

spec:

accessModes:

- {{ .Values.pvc.accessMode }}

resources:

requests:

storage: {{ .Values.pvc.size }}templates/job-workers.yaml

apiVersion: batch/v1

kind: Job

metadata:

name: {{ .Values.workers.jobName }}

spec:

completions: {{ .Values.workers.count }}

parallelism: {{ .Values.workers.count }}

backoffLimit: 0

template:

spec:

restartPolicy: Never

containers:

- name: worker

image: {{ .Values.image }}

imagePullPolicy: {{ .Values.imagePullPolicy }}

command: [”python”, “/app/worker.py”]

env:

- name: POINTS_PER_WORKER

value: “{{ .Values.workers.pointsPerWorker }}”

- name: RESULT_DIR

value: “{{ .Values.resultDir }}”

volumeMounts:

- name: results

mountPath: /results

volumes:

- name: results

persistentVolumeClaim:

claimName: {{ .Values.pvc.name }}templates/job-reducer.yaml

apiVersion: batch/v1

kind: Job

metadata:

name: {{ .Values.reducer.jobName }}

spec:

completions: 1

parallelism: 1

backoffLimit: 0

template:

spec:

restartPolicy: Never

serviceAccountName: {{ .Values.rbac.serviceAccount }}

initContainers:

- name: wait-for-workers

image: bitnami/kubectl:latest

command:

- sh

- -c

- |

echo “[init] Waiting for {{ .Values.workers.count }} worker pods to complete...”

while true; do

succ=$(kubectl get pods -l job-name={{ .Values.workers.jobName }} \

--field-selector=status.phase=Succeeded \

--no-headers | wc -l)

echo “[init] Workers finished: ${succ}/{{ .Values.workers.count }}”

if [ “$succ” -ge {{ .Values.workers.count }} ]; then

echo “[init] All workers completed, starting reducer.”

break

fi

sleep 2

done

containers:

- name: reducer

image: {{ .Values.image }}

imagePullPolicy: {{ .Values.imagePullPolicy }}

command: [”python”, “/app/reducer.py”]

env:

- name: RESULT_DIR

value: “{{ .Values.resultDir }}”

volumeMounts:

- name: results

mountPath: /results

volumes:

- name: results

persistentVolumeClaim:

claimName: {{ .Values.pvc.name }}templates/rbac-role.yaml

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: Role

metadata:

name: {{ .Values.rbac.role }}

rules:

- apiGroups: [”“]

resources: [”pods”]

verbs: [”get”, “list”]

- apiGroups: [”batch”]

resources: [”jobs”]

verbs: [”get”, “list”]templates/rbac-rolebinding.yaml

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: RoleBinding

metadata:

name: {{ .Values.rbac.roleBinding }}

subjects:

- kind: ServiceAccount

name: {{ .Values.rbac.serviceAccount }}

roleRef:

kind: Role

name: {{ .Values.rbac.role }}

apiGroup: rbac.authorization.k8s.iotemplates/rbac-serviceaccount.yaml

apiVersion: v1

kind: ServiceAccount

metadata: